Have you heard of Eleanor Cobham, a woman from fairly humble

origins who became a royal duchess and then lost everything when she was

convicted of witchcraft? Back in the 15th

century probably the last thing you would expect to find in the English royal

family would be a witch. So you may be

surprised to find that several royal ladies from this period were suspected of

practising the dark arts, including Joan of Navarre who was accused by her son

Henry V of plotting to use magic to kill him and Jacquetta Woodville who was

said to have worked with her daughter Elizabeth to bring about her marriage to

Edward IV by using sorcery and making lead images of the king.

|

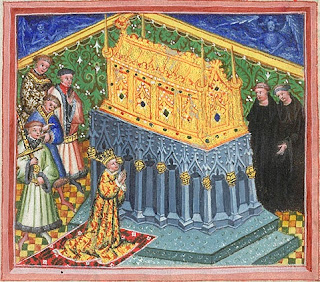

| Eleanor Cobham, Duchess of Gloucester Does Penance |

But how does Eleanor Cobham qualify as a mystery person of

history? Firstly there were the

witchcraft charges brought against her.

Was she really guilty of dabbling in the occult or was she set up by an

opposing faction at court who wanted to undermine the influence her husband,

Humphrey Duke of Gloucester, had over the young King Henry VI. Then there were the two illegitimate children

of her royal husband, Arthur and Antigone Plantagenet. Was Eleanor Cobham their

mother? If so why were they not

legitimised after Eleanor and Humphrey of Gloucester married, as the Beauforts

were when John of Gaunt married his long-time mistress Katherine Swynford?

Eleanor Cobham was born in 1400. Her parents were Sir Reginald Cobham of

Sterborough and Eleanor Culpepper, his first wife. She entered the service of Jacqueline,

Countess of Hainault as a lady in waiting in the early 1420s. The Countess had come to England by the

invitation of King Henry V as she was trying to extricate herself from her

marriage to her politically ineffective husband, John IV Duke of Brabant. She

did manage to obtain a divorce in 1422, although its legality was never

entirely certain, and she then entered into a hurried match with the new King

Henry VI’s uncle, Humphrey Duke of Gloucester, early in 1423. Jacqueline had hoped that her new royal

husband would help her regain her lands in Holland and Zeeland, but Humphrey

was acting as Regent to the new king who was still just a child. The Duke of Gloucester did travel to the

continent with her and they had some success in regaining Hainault, but the

powerful Duke of Burgundy gave his support to her estranged husband John IV.

Jacqueline’s husband Humphrey of Gloucester rather

ungallantly returned to England, leaving her to continue the fight for her

lands on her own. It was the last time

he was ever to see her and many believe that it was during this period in

Hainault that he started his relationship with Eleanor Cobham. Eleanor also returned to England and was soon

openly acknowledged as his mistress. In

1428 Humphrey of Gloucester’s marriage to Jacqueline, who was by this time

imprisoned by the Duke of Burgundy, was deemed to be invalid by a papal

enquiry. The Duke could have remarried

Jacqueline at this point, ensuring that the ne marriage was legal but took the

politically undesirable step of marrying his mistress Eleanor Cobham instead.

His choice did not find favour with the English people. The new Duchess of Gloucester was

unpopular. She was openly criticised

because she chose to live a very lavish lifestyle and was thought to be too

fond of ostentatious displays of pomp and finery. The morals of the ordinary man on the street

were also offended by her having been the Duke’s mistress before he wed

her. She was, however, a favourite of

her new nephew, Henry VI, who gave her expensive presents and gave her a lot of

attention.

|

| Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester |

Like all powerful men, Humphrey of Gloucester had enemies

and political opponents. These were the

years that led up to the outbreak of the civil war that came to be known as the

War of the Roses. Tensions were riding

high at the royal court; having a king who was still a child was always

dangerous as they could easily be used as pawns by the various political

factions, but even as he grew to manhood Henry VI remained a passive,

ineffectual monarch. Not only was Humphrey the Regent, but after the death of

his brother, John Duke of Bedford, in 1435 he also became the heir to the

throne. One of his greatest opponents

was Henry Beaufort, Cardinal of Winchester, who was Henry VI’s

great-uncle. Cardinal Beaufort was determined

to undermine the influence Humphrey of Gloucester had over the impressionable

young King Henry and one of the ways he could do that was by attacking his new

wife, Eleanor.

In June of 1441 a way of destroying the reputation of the Duchess of Gloucester and removing her from public life was found when two men called Roger Bolingbroke and Thomas Southwell were arrested on charges of necromancy and witchcraft. A priest called John Hume informed on the pair, who were said to have been using the dark arts to predict the future of the young king; to find out how long he had to live and whether he would soon suffer a serious illness. They were imprisoned in the Tower of London and it is believed by some that their confessions were tortured out of them. But, fatally for Eleanor, Roger Bolingbroke implicated the Duchess and said that it was she who had asked him to tell the king’s fortune. Also, the Duchess was said to have gone to a witch called Margery Jourdemayne, also known as the Witch of Eye, for love potions designed to ignite the ardour of Duke Humphrey and help her bear a child.

It was alleged they had all met in secret to bring about the

death of the young Henry VI using sorcery, by creating a wax image of him. It is important here to have a look at how

witchcraft and sorcery were regarded in English society in the early 15th

century. Although regarded as a serious crime,

the witchcraft hysteria of the 16th century had not yet swept

through the country. Being found guilty of witchcraft was not usually a crime

that was punished by death unless treason or a murder was involved. Witches could also be accused of heresy, but

at this time heretics who recanted were often also not executed. What made these accusations so serious were

that they involved the king and to try and predict the death of a reigning

monarch using necromancy was treason, which was a capital offence.

Eleanor tried to evade her fate by fleeing into sanctuary at

Westminster, but after Roger Bolingbroke made his public confession in front of

the great cathedral of St Paul’s she was arrested and incarcerated in Leeds

Castle in Kent until her trial in October 1441.

All of them were found guilty and given heavy punishments. Bolingbroke was a known magician and he

pleaded that although he had cast an astrological chart for the Duchess it was

only to predict her future and see how far she would progress in life, and was

nothing to do with the fate of the King.

Although being frowned on by the Catholic Church at the time, many

ladies of the court did dabble in astrology and have their fortunes told. The necessary secrecy surrounding such occult

practices probably gave a frisson of fear to the proceedings that added to the

excitement, but none expected more than a scolding and extra penance if they

were found out. However, his story was

not believed by the court and they found him guilty of attempting to predict

how long Henry VI was going to live. He

was hung, drawn and quartered at Tyburn and was made to wear his magician’s

robes on the scaffold as well as being surrounded by the equipment he used to

do his magic.

|

| King Henry VI of England |

Thomas Southwell was perhaps lucky he died in prison. Margery Jourdemayne was not to be so

lucky. Despite not having been convicted

of either heresy or treason, she was sentenced to be burned at Smithfield. She had stated in court that her involvement

was purely with helping the Duchess of Gloucester bear a child and keep her

husband’s love. She admitted that and image

had been made, but that it was only for the purpose of boosting Eleanor’s

fertility and was not a representation of Henry VI as the court alleged. The harshness of her sentence may have been

down to the fact that this was her second conviction for witchcraft, as she had

previously been arrested and imprisoned in 1430, but it might also have been given

because of her association with the Duchess of Gloucester. A warning of what could happen if you

supported the Duchess and that it was politically healthier to stay loyal to the

Beaufort camp.

Eleanor was not given a death sentence, but she was

imprisoned for life and required to make public penance in three different locations

around the City of London wearing only a sheet and carrying a candle. Her marriage to Humphrey of Gloucester was annulled

on the grounds that is had been brought about by sorcery and therefore the Duke

had not freely given his consent to the match, but had his mind swayed by

witchcraft. Eleanor spent the rest of her life imprisoned in various castles

around the country, first at Kenilworth, then at Peel Castle on the isle of Man

and finally at Beaumaris Castle in Wales where she died. Not surprisingly for

such a tragic figure, after her death her restless figure is said to haunt both

Leeds Castle and Peel Castle in the guise of a large black hound.

We will probably never really know the truth of whether Eleanor

was trying to use witchcraft to predict the King’s death, but in all

probability she was guilty of nothing more than trying to discover her own

future. She was probably feeling very insecure

in her new position of Duchess of Gloucester.

As she had started an affair with her husband while he was still married

to his first wife, she knew only too well that he was a womaniser who was

easily tempted. She would also have been

all too aware that she was not popular with the people and that the Beaufort

faction whispered against her. Bearing a

son would have strengthened her position immeasurably and made it much harder

for Duke Humphrey to cast her off when he got bored of her or needed another

wife to give him an heir, so it is perhaps not surprising that she turned to a

witch for love and fertility potions.

But there is the other mystery surrounding Eleanor

Cobham. Had she given birth to Humphrey

of Gloucester’s two illegitimate children, Arthur and Antigone Plantagenet,

before her marriage? There is no

surviving evidence that she was their mother and, if she had given birth to

them, then why did Duke Humphrey not publicly recognise her as their mother and

legitimise them after their marriage? He

badly needed an heir and there had been a recent precedent set in the royal

family when John, Duke of Lancaster legitimised his six Beaufort children when

he finally married his long-time mistress Katherine Swynford. If they were her children, it also makes it a

bit strange that she was seeking help for her fertility after having already

had two healthy children. Of course,

maybe her husband had already moved on romantically and the problem was not one

of her fertility, but one of keeping her errant husband in her bed long enough

to get pregnant again.

The mysteries surrounding Eleanor Cobham, who rose in the

world to become a royal duchess before becoming embroiled in intrigue and

disgraced for life, may never be fully unravelled. She was probably guilty of no more than

trying to secure her position in a Royal Court full of factions fighting

between themselves for supremacy and control of the king. Unfortunately, it was probably this very

insecurity that worked against her and gave her political opponents the

opportunity they needed to bring her down and also fatally wound her royal

husband’s political aspirations.

Eleanor of Gloucester doing penance image Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Humphrey of Gloucester image Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Henry VI image Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Sources: Richard III, The Maligned King - Annette Carson, Wikipaedia

No comments:

Post a Comment