One of the most difficult choices that any 15th

century English nobleman had to make was where his loyalties lay. In theory it should be a simple matter of

pledging his loyalty to the King, but in the troubled times of the War of the

Roses the political terrain was a great deal more complicated, and there were

tangled family ties and loyalties to consider as well as a duty to crown and

country. In this conflict some men would

lose their lives for their loyalty, some would be executed for their

disloyalty, but there was one nobleman who managed with great dexterity to play

on both sides at once and keep his head very firmly on his shoulders. This politically adroit baron was Thomas

Stanley, 1st Earl of Derby, who throughout his long career would

seamlessly slip between support for the Lancastrian cause and the Yorkist

cause, and then found that he could just as happily embrace the new Tudor

monarchy, just so long as he was well rewarded and retained his titles, estates

and fortune.

|

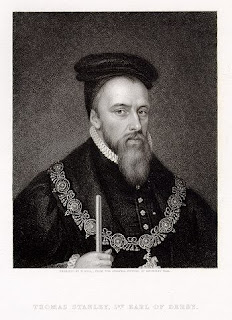

| Thomas Stanley, 1st Earl of Derby |

He was born in 1435 and was the eldest son and heir of Thomas

Stanley, 1st Baron Stanley and his wife Joan Goushill. Through his mother he was related to the

royal family, as she was a descendant of the great warrior King Edward I. The Stanley family wielded great influence in

the North West of England and during his life Lord Stanley would own great

estates, such as Lathom House and Tatton Park, in Cheshire and Lancashire. He was introduced to public life at the royal

court early and in his youth he acted as one of King Henry VI’s squires. He seemed at this stage of his career to be a

loyal and staunch follower of the King, but the political scene in England was

just about to get a whole lot more complicated and Stanley was to produce a master

class in how to navigate your way successfully through tricky, dangerous situations

with your skin in one piece and adding to your power and possessions along the

way. In 1457 he married Eleanor Neville who was the daughter of the powerful

baron Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury.

Her brother was Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick and at this time the

Neville family were strongly promoting the cause of the Duke of York.

In 1459 Stanley’s father died and he inherited his titles

and great estates, including the title of King of Mann. He was now a very important and influential

baron, and one that England’s monarch needed to keep on side if at all

possible. King Henry had been in Yorkist hands since the first Battle of St

Albans in 1455, but the discontent between the two factions rumbled on and came

to a head in 1459, when Richard of Salisbury put his forces into the field of

battle against the King’s men at the Battle of Blore Heath. Henry VI’s French wife, Queen Margaret of

Anjou, was the real power behind the throne, as her royal husband was a feeble

and ineffectual monarch, and had at one time slipped into a catatonic state

that lasted many months. In the male dominated, warrior climate of the late Middle

Ages, the barons respected power, leadership and skills in battle, and as far

as many of them were concerned a simpleton like Henry, whose only interest

seemed to be religion, just did not cut the mustard, and his closest supporter

were thought by the Yorkist faction to be corrupt and avaricious.

Margaret of Anjou wanted her husband back as he was an

important part of her power base, and gave orders that Stanley was to raise an

army to stop Salisbury, who was marching through the Midlands, from linking up

with the main Yorkist forces in Ludlow. But although he had 2,000 men-at-arms

at his disposal, he chose to sit the battle out. His brother, Sir William Stanley, threw his

hat into the ring and fought on the side of the Yorkists and got attainted for

his troubles. That Lord Stanley was

secretly supporting the Duke of York and his faction, is borne out by

allegations that he had managed to prevent a number of Cheshire levies from

fighting on the Lancastrian side and had also managed to covertly help the

Yorkists. Blore Heath was a savagely

fought and bloody battle that was won by Salisbury and cost the life of the

Lancastrian battler commander Lord Audley.

However, just to make sure that he was covered on both sides, after the

battle Lord Stanley sent his congratulations on the victory to the Earl of

Salisbury and wrote to the Queen to offer his apologies and excuses for why he

had not seen fit to commit his men to the battle. Margaret of Anjou cannot have

been too convinced or impressed by his explanations, but nevertheless when

Parliament petitioned for his attainder later that year they were not

successful; in the fluctuations of the Wars of the Roses she needed all the

friends and support that she could get, even those as unreliable as the

slippery Lord Stanley.

Lord Stanley joined the Yorkist Council soon after the

Battle of Blore Heath, when Richard, Duke of York dropped his bomb shell that

he wanted to claim the crown of England himself, rather than just be the most

influential baron guiding Henry VI’s royal career. This naturally did not go

down well with Margaret of Anjou, who wanted the English throne for her young

son Edward of Lancaster. She managed to eliminate her nemesis the Duke of York

and his key supporter the Earl of Salisbury at the Battle of Wakefield in

December 1460, and had their heads put on public show on the Micklegate Bar in

York, along with those of York’s son Edmund, Earl of Rutland and Richard Hanson.

The Queen’s forces defeated the Earl of Warwick at the second Battle of St Albans

early in 1461 and regained possession of the King, but were then decisively

defeated in March of the same year by an army led by Edward Earl of March, the

Duke of York’s eldest son. Edward had

himself crowned as King Edward IV and Margaret, having once more lost possession

of her husband, fled to France via Wales and Scotland. Lord Stanley had

demonstrated his usual survival skills and had not fought at either Wakefield

or Towton, though he had aided the Earl of Warwick in besieging some northern

castles that held for Lancaster. The

Earl of Warwick was now one of the most powerful men in England, as well as

being Stanley’s brother-in-law and it seemed that at this time the two powerful

barons enjoyed cordial relations.

However, as history was to show, family loyalty would not be enough to

ensure Stanley’s support, as this was a man who always liked to come out on the

winning side.

The honeymoon period for the new Yorkist monarch was not

destined to last for very long, as fractures in the relationship between Edward

IV and Warwick soon began to show.

Warwick was known as the ‘Kingmaker’ and expected to be well rewarded by

the new monarch as well as to be the key influence on royal policy. But

although he was young, and grateful for Warwick’s aid in putting him on the

throne, Edward IV had a mind of his own and liked to make his own choices. While Warwick was trying to secure a

diplomatically useful match for him with a French princess, Edward was dallying

with a Lancastrian widow behind his back. He married this widow, Elizabeth Woodville, in

secret and when Warwick found out he was furious. Further salt was rubbed in his wounds when

Edward IV started arranging very favourable matches for her very large family,

some of which were detrimental to Warwick’s own family. Lord Stanley was

married to Warwick’s sister Eleanor Neville, but when Warwick, aided and

abetted by Edward IV’s own brother the Duke of Clarence, rebelled in March

1470, Lord Stanley did not step in to help him. Stanley then did an about turn

when Warwick, having fled to France and allied himself with Margaret of Anjou,

returned in 1471 to England to place the hapless Henry VI once more on the

throne. To all outward appearances it seemed as though Lord Stanley had thrown

his lot in with the Lancastrian cause, but as usual looks were deceiving. His brother William hastened to Edward IV’s

side when he landed at Ravenspur to reclaim his throne, but as usual big

brother Thomas hung back and took no part in the Battle of Tewkesbury which saw

Margaret’s forces decisively defeated and the young Edward of Lancaster killed.

The newly restored King Edward IV decided to give the

powerful magnate the benefit of the doubt, and rewarded Stanley’s

non-participation in the conflict by appointing him steward of the king’s

household and inviting him to sit on the royal council. Very conveniently for him, his ties to the

dead and discredited Earl of Warwick were severed when his Neville wife Eleanor

died in 1472. He promptly married Margaret

Beaufort, the dowager Countess of Richmond.

This was not an obvious match for a supposedly fervent supporter of the

Yorkist monarchy, as her son Henry Tudor was the last surviving Lancastrian

claimant to the throne and was living in exile in Brittany. However, throughout

Edward IV’s reign he played the part of a loyal subject, accompanying his King

to France on campaign in 1475 and being awarded a pension by the French king

Louis XI at the treaty of Picquiny, and he also fought in Scotland with the

king’s brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester in 1482, and helped him capture the

key town of Berwick-upon-Tweed.

It was the unexpected death of Edward IV in 1483 that once

more upset the political apple cart. The King’s heir was his eldest son, who

became Edward V. His uncle, Richard of

Gloucester, had been appointed Lord Protector and arranged to meet the

delegation, including several of the new king’s Woodville relatives, who were

accompanying Edward V to London at Stony Stratford. A fracas broke out, and the

Duke of Gloucester secured possession of the new monarch and took him to reside

in the Tower of London. This was not the

odd choice that it may seem, as the old Norman fortress was where monarchs

traditionally lived in the days before their coronation. Elizabeth Woodville had fled into sanctuary

at Westminster with the rest of her family, and there were repeated rumours of

plots and conspiracies. One of these

erupted in June 1483 when Richard stormed a royal council meeting being held at

the Tower and arrested several of the noblemen in attendance. Lord Stanley was injured in the ensuing

scuffle and briefly imprisoned, but Lord Hastings was condemned on the spot and

summarily beheaded.

Richard seized the throne for himself and was crowned King

Richard III. Lord Stanley had obviously been fully forgiven, although maybe not

entirely trusted as his eldest son Lord Strange was married to a niece of

Elizabeth Woodville, as he was allowed to carry the mace at Richard’s

coronation and his wife, Margaret Beaufort, carried Queen Anne’s train. He was also allowed to carry on in his role

as the steward of the king’s household and joined the Order of the Garter,

taking over the executed Lord Hasting’s vacant stall. This was an age which did not allow for

sentiment, and Lord Stanley was not a nobleman who would have worried overly

much about sitting in a dead friend’s chair.

His survival skills were once more called upon late in 1483, when King

Richard’s closest advisor, the Duke of Buckingham rebelled. Despite the fact that his own wife, Margaret Beaufort,

and her crony Morton were deeply implicated in the plot as they were brokering

a marriage between Elizabeth of York and Henry Tudor, Stanley and his brother

William helped the King suppress the rebellion.

The Duke of Buckingham lost his head, Margaret Beaufort was formally

placed in her husband’s custody to keep her out of trouble, Morton had to make

himself scarce and once more Lord Stanley was lavishly rewarded with estates

forfeited by the rebels and Buckingham’s position of High Constable of

England. It was perhaps the biggest

mistake that Richard III ever made that he did not execute Margaret Beaufort

and put an end to her intrigues and plotting on behalf of her son Henry Tudor,

but although retribution for men was often swift and savage during the Wars of the

Roses, executing nobly born women would not become the rage until Tudor times.

Richard III endured the death of his only son and heir and

then his wife Anne Neville during his short reign, and then in 1485 he had to

face an invasion by the forces of Henry Tudor. Lord Stanley asked permission to

leave court at this time, but Richard evidently did not trust him as he made

him leave his oldest son Lord Strange in custody as a pledge for his continued

good behaviour. Both he and his brother

William were, however, in contact with Henry Tudor when he landed in Wales and

without Sir William’s lack of intervention his forces would never have been

able to progress into England as they did.

Both the Stanley brothers were ordered by King Richard to raise an army

to support him, and when the King discovered that Sir William had effectively

cleared the path for Henry Tudor, he ordered his older brother to join him immediately. Lord Stanley suddenly discovered that he was

too unwell to answer his King’s summons and when his son, Lord Strange, was caught trying to escape from Richard’s

clutches, he admitted that both he and Sir William had been plotting with Henry

Tudor. It has been said that Richard III gave orders that Lord Strange be

executed during the Battle of Bosworth, to which Stanley’s response was reputedly

‘Sire, I have other sons’. Fortunately

for Lord Strange, the orders were never carried out.

So there were four armies headed towards Bosworth on that

fateful day in August 1485, Richard III’s, Henry Tudor’s, Sir William Stanley’s

and Lord Stanley’s. Take a guess as to whose army once again didn’t take an active

part in the battle? As had happened several times before, Lord Stanley kept his

fighting men out of the proceedings, although it is thought that he may have

met with Henry Tudor on the eve of the battle. Sir William was once again a

little bolder and intervened in the fighting and helped win the day for Henry

Tudor. King Richard III was slain in the fighting, and Lord Stanley, despite

his earlier absence, was conveniently on hand to pick up Richard’s fallen crown

and place it on the head of the new king, Henry VII. In a move that perhaps signalled the future ruthless

nature of the new Tudor dynasty, Henry VII conveniently dated the start of his

new reign to the day before the Battle of Bosworth, declaring all those who had

fought against him traitors. So Lord Stanley’s stepson was the new King of

England and as usual he reaped the rewards, becoming Earl of Derby in October

1485 and in the following year he was confirmed as the High Constable of England

and appointed High Steward of the Duchy of Lancaster. When Henry VII’s first son was born in 1486,

he was chosen as godfather for the infant Prince Arthur, and it looked as

though from that point on life would be relatively plain sailing for the all powerful

baron.

However, the Yorkists had not quite yet run out of steam and

in 1487 a rebellion was raised in support of a pretender called Lambert Simnel,

who was supposedly Richard, Duke of York, one of the Princes in the Tower. Henry Tudor must have been quite relieved

when Lord Stanley did actively participate in putting this rebellion down, and

did not stand aside hedging his bets as usual.

After the Battle of Stoke, he once again reaped great rewards for his

assistance and was given lands forfeited by the rebels, which included the

estates of Francis Viscount Lovell, Sir Thomas Broughton and Sir Thomas

Pilkington. He once again in 1489 helped the Tudor monarch to suppress a

rebellion in Yorkshire, but his brother Sir William Stanley eventually slipped

up by backing the wrong side when he fought for the pretender Perkin Warbeck

and was executed for his treason.

Lord Stanley died at his estate of Lathom House in Lancashire

on 20th July 1504, and was buried among his ancestors in the family

chapel of Burscough Priory. His eldest

son Lord Strange had already died, so he was succeeded by his grandson Thomas,

who became the 2nd Earl of Derby.

For a nobleman who had played such a prominent political role throughout

the Wars of the Roses, he was very fortunate to have died naturally at home,

instead of on a battlefield or on the scaffold.

It had taken great skill to not only have stayed alive, but to have

enriched himself and his family in the process, even though no monarch, however

powerful, could ever completely rely on his loyalty or support. Expediency was his watchword and Lord Stanley’s

allegiances would shift in the winds of change, always ready to altered and

adjusted if the situation demanded it.

No comments:

Post a Comment